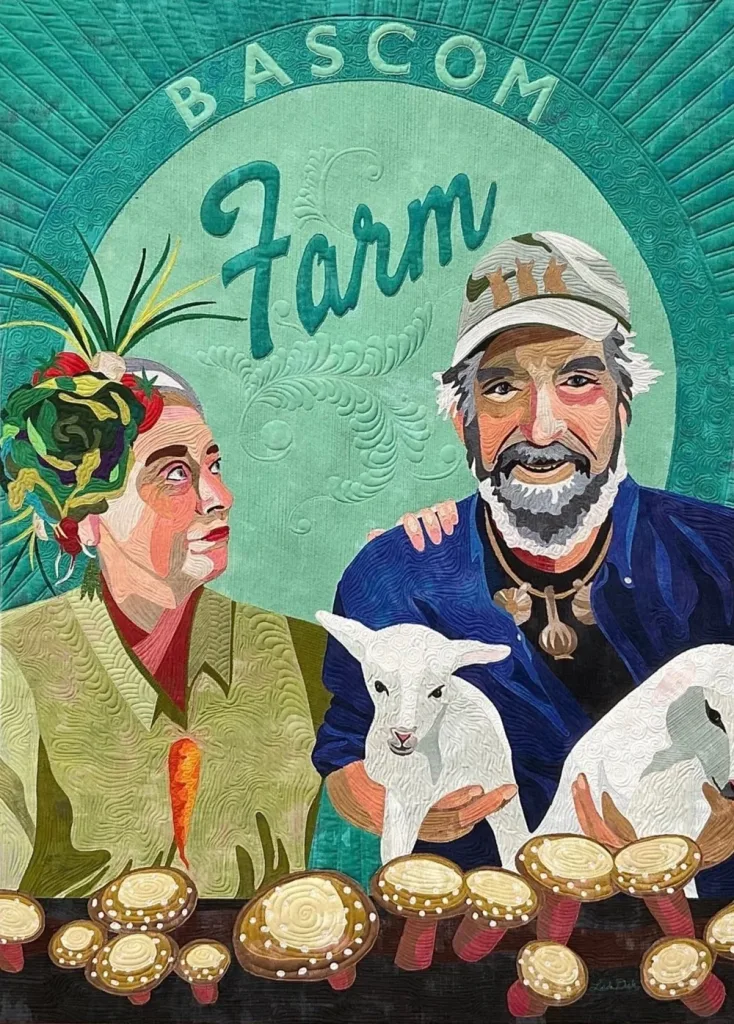

Linda Diak: “An art quilt can be anything it could be, and the quilting can really advance the story of the piece”

Linda's art quilts are exquisite, and her lessons about how one can survive as an artist, no matter what, don't simply talk of experience but of wisdom. Listen (and read) well.

Linda, now an award-winning art quilter, has been many things in life, but always an artist. She was a fireworks importer, worked as an administrative assistant, and even owned a Christmas store at one point. But as she says, “I always found a way to work art into it…I need to be making stuff. I don't know what else to do”.

I genuinely believe that every creator would benefit from reading this interview with her, or from getting to know her personally (if you’re lucky enough to!), because she has: the stories, the lessons, the advice, and most importantly, the attitude. The attitude that she describes as “Sometimes there is no solution. There's no fix. You're screwed. But you still have to come up with a next step”.

And that is what she’s been doing all her life and what she keeps doing now, despite everything. And I mean, despite everything—because to me, it feels like she’s been through nearly everything. Yet, true to her own advice, she keeps fixing things. She keeps fixing life and breathes that into her art quilts, too.

Tell me the story of when you figured out that quilting was the thing for you.

About five years ago, I was in a quilt shop that started carrying the longarms. I sat down at a Bernina Q 20 and started playing with it. Within 10 seconds, I looked at my husband and said, “I can be really good at this, and this is what I’m going to do”.

First, I had tried the traditional forms of quilting. Once I was in another art quilter's studio, and I told her I knew I was going to be a quilter during this period of my life, but I didn't know what kind.

Around that time, a gentleman who had a restaurant right down the street from our house had purchased a Robin Arthur painting with the rights. The painting was very small, though, too small for his restaurant to make a statement. I don't know why, but I said, “Hey, Jason, let me quilt that for you”. And I did, and I had so much fun. And so away I went.

Have you been an artist all your life?

I was a weaver for the first 32-33 years of my life. Then I began spinning, which is when I started Grafton Fibers with my partner, Tom, which later became DyakCraft [where you can get the world's finest hooks and needles], and we’ve had that for 25 years now. I've always been involved in the arts, but always in fibers.

What was it like when you started your journey as an artist, and especially when you decided that you wanted to make a living out of being an artist?

Well, weaving was a long time ago, but this time around, when I started quilting, I brought a lot to the table that most artists don't necessarily have when they start, if they're starting in their late teens or twenties or whatever.

By then, I had a lifetime of retail experience, mail order experience, catalog experience, and I had the ability, I had the knowledge, and the awareness.

Your life experiences add up. Like how when I had Christmas stores, which had nothing to do with fibers, I learned that they’re all about presentation. For those, I had a crash course on presentation and on a massive level. It was a long time ago, but it sticks with you.

In the late '70s, early '80s, I ran a photography firm. I wasn't a photographer, but I gained a great deal of knowledge from our photographers. It all adds up.

How did you end up running a photography firm and having a Christmas store?

For the photography firm, I answered an ad for an administrative assistant in Atlanta. I was 18 or 19. They would go to photograph conventions around the United States and sell that way. It was owned by a husband and wife, and they mostly needed somebody to man the fort when they weren't there, because they were traveling often, and that was me.

I remember that somebody once came to me and said, “You have to do payroll”. And I said, “I don't know how to do payroll”. So, I went through the checkbooks and figured it out. There was no Google back then. You couldn't just go online. And I just figured out mathematically what the rates were and the deductions, and so forth.

As for the Christmas store, I had that with my partner at the time. We were fireworks importers. Don't ask me how that started. 😅 We wanted to be able to retain our core staff year-round. We hired about 200 and some people seasonally, but we wanted to grow a core staff for accounting, for sales, and so on. And we figured that the opposite seasonal thing was Christmas. That's how I ended up with that.

Do you remember what was the first thing that you sold as an artist?

That would be my weaving, but in this round, for quilting, the first thing that I sold, technically, was to one of our knitting needle customers [at DyakCraft], who reached out to me and commissioned a piece for her home. I had an advantage there by having a core group of customers already who’ve purchased from us for years and liked our work.

Do you think it changed how people see what art is or how people look at art, and what their definition of art is, since you've started?

People are intimidated by art. Unless they're into art or studying art or collecting art. And even a lot of the collectors don't know what they're collecting. They hire somebody to come tell them what to collect.

But, fiber art in general, and quilting in particular, are more accessible and approachable. People can relate to quilts. And even if the quilt doesn't look like the quilt on grandma's bed or their bed or whatever that they grew up with, it's a quilt.

They’re particularly drawn to the pieces I do, the bold imagery of mostly animals. And as they get closer, they realize, “Oh, that's sewn, it's a quilt”. And so they will spend time studying it, studying more than they would if it had just been a painting of a chicken or a dog.

I also think that quilts will draw people into spaces that they otherwise wouldn't venture. A lot of people aren't going to go spend time in galleries or museum spaces because they don't feel they have the knowledge. Even if they're educated, they don't feel that they're educated in the art. They feel intimidated, but the quilts draw them in.

Do you think you could highlight one thing or even just a few that you think have definitely helped you stay in the art business?

I don't know what else I’d do, honestly. I don't know what else I'd do at this point.

I’ve held other positions in my life, but I always found a way to work art into it. When I worked for the botanical garden in Atlanta, I was hired to be an administrative assistant, which isn’t very arty, but I spent a decent portion of my days making individual, artistic buttons for the volunteers or making posters for the educational department for their programs.

I need to be making stuff. I don't know what else to do. Anything I do is going to end up having me make stuff. I'm 65, I'm not going anywhere at this point. This is what I'm gonna do unless it's taken away from me somehow.

Let’s talk about marketing art and how that has changed from the time you started til now.

Well, a lot changed. We've tried many things along the way.

When I started Grafton Fibers [forerunner to DyakCraft], we were the only ones with a website in this area. I sat up until 2-3 o'clock in the morning with the tech from the phone company, trying to figure out how to get the thing published. At around 2:30 in the morning, it went live.

We were early adopters of eBay. We had one of the first eBay stores. We tried Etsy when it was new.

We've tried all these different things over the years, and in the end, what works most is what works for any business. And that is that 60% of your marketing should go to the people who are already your customers, which is really difficult for people who are new and just starting. So you have to try a little of everything. But do the thing that you like doing the most because it's repetition, it's consistency.

If you hate making videos, then don't go on TikTok. If that's what you like to do, then that's where you should be. But don't try to force yourself to do methods that don't appeal to you personally.

Do what appeals to you as a customer. If what appeals to you as a customer is a finely crafted story in your inbox, then do that and build on that.

That's my best advice after all these years of promotion.

The other thing that I think is really important is that people buy our needles [at DyakCraft] because they are the best needles in the world, but people really buy our needles because they want to support us. It's us. People buy my quilts because they're beautiful, but above that, people buy my quilts because they want to buy my quilts.

Most of my work is commission work, so they're buying a piece of me when they commission work from me. Same with any artist. So the challenge there is to give enough of yourself to the public that they can form a connection with you, but not so much that you feel like they need to know every waking moment of your life.

And that's a line that most people have never had to draw, and so it takes some finessing. Whereas the older folks have to dial it up, the younger ones may have to dial it down a little and find where that nice balance is between having enough of your personality or at least your art personality. It doesn't have to be all aspects of your life out there for your customers to connect to.

Oversharing drains the artist.

What would you do in terms of promoting and marketing yourself if you were starting out now? As you mentioned, you already have a core base of customers, but if you were a total beginner right now, what would you do? I partly understand the pressure new artists feel about social media and how they are supposed to post as quickly or as frequently as they can. It’s hard to get noticed.

It is. It's very hard to get noticed. I mean, our website 20-some years ago had over a million visitors a year. I've never gotten anywhere close to that since because everybody else got online. It was easier back then. There weren't many people online comparatively, and there certainly weren't many businesses online.

Now, I think YouTube is really powerful, and if you're going to focus on anyone, I think that I would focus there. I have one, but I'm bad at it, and I don't really do it.

But that would be the one I would learn first because people are using it for more than just watching videos; they're using it as a search engine. Even if you learn to make stop motion videos of your art-making process, that’s okay. It doesn't have to have your face, doesn't even have to have your hands.

Facebook has changed dramatically since its inception, and it changes every three to four months now. Instagram is constantly changing, too, as to what works and what doesn't work.

Threads hasn’t gotten any traction at all. I will say that Bluesky is one of the newer ones that has gotten some traction, and it’s been a better platform for a lot of things, for my quilting, especially. But all of those, basically, are the same. So once you learn one, you can kind of feel your way around the others.

At the same time, don't sweat the Facebook and Instagram thing. People think that those numbers have to be there, and they don't. I get more traction and more business on a fraction of the followers for our knitting needles than a yarn company or a pattern designer who has tens of thousands of followers, and I have like 4,000.

You know, back in the day, when I used to advertise on Facebook, I could tell you the hour that the ad stopped running because the sales stopped. It hasn't been like that in a long, long time. The Instagram ads? Nothing. Nothing beyond what we'd normally get from just a post. Same on Facebook.

On Instagram and Facebook, it’s really hard to grow organically if you start now.

For a new person in art, you're better off spending the money on your website and building out your website, and if you don't know how to do it, then spend some money on somebody who does. But when it comes to growth, the question is, what kind of growth do you want? What percent of people are you bringing back each week?

On Facebook, I have about 150 to 200 people who follow my page, and I can count on those 150 to 200 people.

You have to build community. I don't care for Instagram as much for community building, but I try to make sure to go through it each week, and like and comment on the things I see. The quilters, the knitters… And it means a great deal to them.

If I have something I need to ask, if I have something I really want put out there, if I have a problem, I can count on that core group of people, and I can count on the fact that they will share my work elsewhere. I can count on them sharing something that I need to be shared.

And you have to put in the time for that. I think that's time much better spent than on advertising dollars. They can say it's quicker to buy an ad. Well, not if you think about how much you had to work and then market and then sell in order to have the money to pay for that ad.

But that's the problem, though. Artists value their time, but they don't place a value on their time. And that's something that artists need to do. Then you can start realizing time spent doing this, time spent doing that, and what it is actually costing you.

Pricing art in general seems very problematic for so many people.

What I see is that they don’t factor in studio time, which is a problem because art is subjective. One person could look at a painting and say, “Well, that's a ten-thousand-dollar painting. Another one would look at it and say, “Oh, that's so pretty, I'd pay 500 for that”.

Art is very subjective. But, for a baseline, no matter what you're doing or making, you need to know your studio time. And that is all your expenses to have and maintain your studio for a year, divided up by the number of hours you spend in it, not by the number of hours in a year.

That's what a lot of people think, like “The studio costs me 5,000 a year”. No. It costs you 5,000 a year, divided by how many hours you are actually in it. And if the studio's in your home, what percentage of your home is taken up by this? What percentage of your electric bill or heating bill, or water bill goes towards it?

Put those in there and divide them by the number of hours you're working, and you'll have a studio fee. Most people's studio fee is going to come in around 45 to 75 dollars an hour. So right there, you know where to start pricing your art.

Has anybody ever said that your prices are maybe too high, and they refused to buy something you made because of it?

I’d hear things like “I could get that at Pier 1”. Well, no, you can’t. But the point is, they're not your customer. They are not your customer.

I know that it's really hard when you're hungry, and we're always hungry, so I totally get that. It's really hard sometimes not to say, “Oh, okay, here’s a reduced price”.

You know, I broke my arm last year very badly, and that meant I was out of work. Not only that, but I had to pay other quilters to come in and finish the work I had in-house for other people. So I had a sale of my quilts, and I sold a lot. It helped us get through.

It's really tempting to reduce prices, because nobody's really buying art right now. It's been really fraught, and it's really tempting to have a sale again. But that doesn't sustain; that's a bad habit. It's something you pull out once in a while when you need it.

There's going to always be highs and lows. So it's really, really important to know what it costs you to produce your work. If you don't know, you're going to sell it for less than it cost you to make it. And now you might have some money in your pocket, but you just lost money.

But there are always people with disposable income, and that’s what artists need to remember. You have to keep working at it, and you have to go get a job if you need to, to supplement during the dry spells. Write articles for publications, give talks if you don't want to get a 9-to-5 somewhere. There are ways of supplementing your income so that you can maintain your price. But don't try to off your work.

I have print-on-demand stuff on my website. I didn't put up everything under the sun you could print an image on. I just put up the things that the printing company did well. Honestly, I'm shocked at how nice these pillows are. I put those up, and they pay for the website, even though I don’t promote the merchandise other than maybe once every three or four months, which means putting it on Instagram and sending out an email to my customers that I have a batch of new things. And, I usually see a spike around the holidays.

I could sell a lot more if I sold stuff the way a lot of vendors sell print-on-demand merchandise, which is that they only mark things up by $1, $2, $3, or $5, but then you're relying on quantity. And if you're going to rely on quantity, you'd better be marketing it. I don't want to spend my studio time marketing mugs. This is not going to happen. So mine have a full markup on them, which means when I sell something, I get 30 to 40% on some of the items.

I also added a class this year to my site and had to start paying more for hosting, but the mugs and pillows still cover that.

And that's the other thing I would say to people. One of the things that survives in an economic downturn is cheap entertainment. So if they can make classes, not for a thousand dollars, you know, but $10, $15, $20, or $30 classes, and short classes, people will see it as good entertainment.

What made you create that class?

Fifteen years ago, in our kitchen, I turned to my husband and said, “We have to start selling information because we're not young”, and we were 50 at the time, and we just didn't do it.

I finally have the one class now, and my goal is to produce more, shorter, less expensive classes because the people who have taken my class will likely take more of my classes because, again, they're shopping because of me.

I was nervous about doing it, but everyone I've spoken to about teaching said, “You know, everybody can teach you how to do a half square triangle and quilt it, but they're coming to you because they want to hear it from you”.

The other thing I started doing that I didn't know there'd be such a demand for is Trunk shows. So, I can show people my pieces, live or on Zoom, explaining my methods, and they can ask their questions. It’s tailored for groups or guilds.

Something like this, again, can supplement your income. Guilds might pay you three or four hundred dollars for a presentation. If you can add that up over the course of a year, you might end up with an extra five grand or so from just making Zoom presentations to groups.

Do you see a crossover between the people who buy your quilts and those who buy a pillow or a mug from your store?

Yes. And on top of that, when I do a larger commission where they're spending 3- $4,000 on a quilt, I will send them a pair of mugs with their quilt on it. They really like that. It means I've spent an extra 20 bucks on that customer, but I’ve got a really nice commission product, and that keeps them advertising to their friends.

Another time, I had a customer who was also a friend and a customer of DyakCraft, and she wanted a quilt of her dog who passed away. I went ahead and drew up the photo into my pattern, sent it to her, and she said, “That would be great, but I can't now, we're trying to buy a house. I can't buy it now, but someday I'm going to”.

So I had that image printed on a pillow for her because I knew she really missed her dog, and I was able to send that to her. And, sure enough, a year later, she came back and commissioned the piece.

That's not something I do for every customer, and I wouldn't recommend that to people, but sometimes it's just about being helpful. And I didn't do it for her to get her to give me money. I didn't think she would do that, actually, because I knew she had a lot of outlying expenses. I did it to make her feel better, but it did end up meaning I got that quilt commission. So, you never know.

Do you have any seasonality, regular ups and downs, when it comes to selling?

You have to get ready and prepare for that. This is the reality of it. Unless you're in museums selling paintings for millions of dollars. And that's why you need multiple streams of income.

You must be ready for outside influences. Hurricanes, pandemics impact what and when people shop as well as recessions. You have to have something else going for you.

When our DyakCraft products were copied, it was brutal in every way, including financially, of course. I was borrowing money to feed my kids. You have to get through stuff like that; you have to be willing to try. And so I did. I opened a studio. I did 22 shows coast to coast, selling our goods, which was really exhausting.

But I had to do all these things to survive.

You’ve talked about online promotion, but what are your thoughts on offline promotion?

It’s important to get your work out there.

When I made that piece for that restaurant, when I started quilting, a new flower shop opened on the same street. At the time, I was practicing quilting these flowered panels to learn how to quilt, and I gave the final quilt to the owner.

Then, a friend opened a bookstore, and I made her a quilt to celebrate her store. Then her son, who had a pie shop, got jealous that I made his mom a quilt, so I made him and his wife a quilt for their business.

With each one of those quilts that I did for the stores, I tried something new. I viewed them as classes. And, everybody's got a quilt from me, and everybody in the community rapidly knew I quilted. I also made a quilt for our library. And now I have a library in Massachusetts that wants me to do one for them.

You mentioned using Etsy before. What were your reasons for leaving it?

In the beginning, it was a great place. Now, I could put my works on Etsy and sell them, but I’d be losing 25 to 30% by the time all the fees and everything were paid. And is it worth the hassle? No. I’d be losing money on every one of those sales.

There was also the time when I used to make spinning fibers, carded fibers, and I created a method or style of doing it, and I could produce a different look. The way I blended fibers and the way I photographed them were distinctive at the time. I kind of set the standard for that. Within a week of putting the first Etsy listing up, it was copied everywhere throughout Etsy.

I said, “I’m not going through all this work for that”.

It wasn’t just Etsy, though. Everybody was copying everybody back then. For instance, I shut down my blog. It was just providing content to other bloggers. But I didn’t want to do all the work so others could have content.

I used to have 30 pages of instructions on our website and all kinds of things related to knitting, crochet, and weaving. I ended up removing it because it started showing up as magazine articles. They didn't have AI yet to write their articles for them. I just didn't feel like I needed to spend what time I had creating content for other people.

Let’s steer to a more positive topic. Your “Oh, Canada” art quilt is featured in a quilt show this year [between June 18 and September 1]. How did you get that opportunity?

[The Oh, Canada art quilt won Best Original Design at Billings Farm Museum’s “A Vermont Quilt Sampler”]

You just submit your work to a show like that, like you’d do it with any other. I do get asked sometimes and have requests from other art quilters who are curating a show like that, but otherwise, I do submissions.

That particular show, where the Oh, Canada quilt is featured, is in a farm museum in Woodstock, Vermont, part of The Rockefeller Foundation. They’ve always had a quilt show each year for the quilters in our county, but there were fewer and fewer quilters who entered over the years. Now they hired a new exhibitions person who has a background in art museums, and he wanted to breathe new life into it. He wants to present what Vermont is doing in quilting, and he does a beautiful job.

When it comes to art quilts… You have an art quilting service, too. Can you explain how that works, especially compared to taking commissions?

There’s this really common thing that people make the tops of the quilts, and they send them to quilters to quilt.

People do not generally like to quilt art quilts because of how they're constructed. They could be constructed in all different ways, and therein lies the problem. Weird materials, certain difficulties, and challenges presented with them… But I like art quilting. I love it.

Because quilting bed quilts, for instance, is fun, but it's a lot of repetition, they're usually symmetrical, a lot of triangles and squares, whereas an art quilt can be anything it could be, and the quilting can really advance the story of the piece. Quilting can transform a bed quilt into a thing of absolute stunning beauty, but it doesn't change the story usually much. And with art quilting, it does. I love doing that.

There are also people who like to construct, but they don't have or don't feel they have the skills to do the thread work, so they send it to me, and I'll do it because I like it.

When it comes to commissions, how many do you usually do in a year?

On average, it would probably be six to eight. What I noticed was that overall, the commissions got more frequent, but smaller scale, instead of how people usually start out with new artists, asking for small pieces and then eventually for bigger ones. It went down, and I think that was really a function of the economy. Art contracts when the economy contracts.

Where are your customers located?

For the quilting, they're in the US, because it’s too expensive to ship. Over the last seven years, shipping has increased dramatically, and the pandemic put it through the roof, then it settled down a little, but it's gone way back up.

Years ago, when we started our needle business, it was cheaper to ship to Canada than to California. 25 years ago, it cost $3 to ship a small box to Canada and $5 to ship it to California. The tables have wildly turned. It's just prohibitively expensive.

There are also the quilt shows. I have one big quilt that I would like to show more nationally, but it would cost me over $200 one way to ship it, and I just can't afford to do that. It’s a common problem for quilters because quilts are not paintings. They are heavier. They’re bulkier. But even the painters and photographers, if their work is framed, the shipping is getting to be too much, so it’s more of a general concern now.

Do you do financial planning and review reviews?

Our financial situation has been precarious, actually, throughout the last 25 years. The last few years have been very difficult. My husband had hand surgery, then I broke my arm, and we’ve been running on a wing and a prayer for the last few years.

In terms of knowing our inventory and our values, we're in a different position than most artists. We have a lot of business insurance. We have two locations: the house here, where we do most of our work, and my husband has a wood shop in another town. There's a lot of equipment involved in what we do.

I added insurance to the art quilts that go out into the world, as well as the ones that are here in the house, because most venues will not insure them far enough or fully enough. Some will only insure them for $1,000, no matter their value. Some for $2,000, some won't insure them at all.

My business insurance now is over $450 a month. It's a lot of money when you're scraping. It's a lot of money, but it’s worth it. I’ve done many shows by now, and I’ve seen terrible things happen. One time when we were doing an art festival, the wind picked up a light booth and set it down on another glass one. It was a very expensive day for both of the owners.

Do you have advice about how one can handle and overcome setbacks as an artist?

It's all attitude. It's really easy to wake up with a panic attack or go to sleep with a panic attack. And the worst thing about that anxiety and stress is that it's a physical killer and it's a creative killer. And you cannot find solutions or ways out of a predicament if you're freaking out over it.

Of course, it's so much easier said than done, but I guess you need to build a toolbox and you have to continually add to it and take out from it, things that work and don't work.

I can say that now from the vantage point of having aged. Things that I used to be able to accomplish, I can't physically do anymore. My brain might be willing to, but I'm also tired.

So, you have to constantly change your toolbox, whatever that means to you. Listening to classical music or rock, or reading a book that has nothing to do with what you're doing, just because it inspires your imagination.

Anything that will take you out of the fight or flight mode will allow you to come up with creative solutions. And sometimes there is no solution. There's no fix. You're screwed. But you still have to come up with a next step.

You still have to say, “Okay, I’ve got to get a job. So what does that entail? Do I want to keep doing this [art]? I do, but I really absolutely have to get a job”. So then what kind of job do you want to get? Do you want to get a job that makes you the most money, or do you want to get a job that, when you walk out the door at the end of the day, with no extra responsibilities behind, so you can focus on your [creative] work?

All those questions have to be answered individually because they're different things to different people. But it's the toolbox that allows you to do that and make those decisions.

What was it like for you to reconcile your roles as an artist and a mom throughout your life?

It was a challenge when my kids were small. When I started Grafton Fibers (forerunner to DyakCraft), shortly after that, we got the farm. I had sheep, llamas, chickens, dogs, cats, rabbits, and our three little boys, and on top of that, I was doing shows across the country. That couldn't have happened without my husband.

Your support doesn't have to be your husband, but you have to have support. I was fortunate it was my husband. He’s always been extremely supportive of what I do and appreciative of what I do. But, although I had his support, it was a challenge.

It was difficult and it was exhausting, but at the same time, I had what a lot of people, particularly women, don't have, which is someone who really believes in them. You need to find that person. It can be a partner, a spouse, it can be a neighbour, it can be somebody in another country that you meet with on the internet. It can be anybody, but you need that person.

What do you think is the biggest challenge for creators today?

From my perspective, my biggest challenge is maintaining confidence. I have my husband, and I have my people out there who tell me I’m wonderful, but it’s hard.

Your artwork comes from within, and inside we have all kinds of voices, and it's the anxiety voices and the fear voices and the “you're not good enough” voices that like to join together and make a chorus. You really have to find ways, again in that toolbox, to diminish them.

So, that's the biggest challenge for me. I have the knowledge I need to succeed. I have the skills I need to succeed. I have the talent I need to succeed. I just have to believe in myself.

I thought you were going to say that it's the economy again. 😅

It really depends on what you're doing, and it could be that what you want to do, whatever it is, is just not going to cut it, no matter how good you are. That happens. There are a lot of wildly talented people doing incredible things who have never been able to monetize. It doesn't mean what you're doing isn't of incredible value, though, or beauty.

I think stress can be a great motivator; financial stress, in particular, can be an incredible motivator—just as much as it can be a killer. I'm also not advocating for you having absolutely no stress in your life or no challenges in your life because that's all part of life, and that's what informs what we do. But you need to have as many ways as you can of coping with it. And coping with it might be getting a job.

You know, economic downturns aren't necessarily the worst thing. I think the worst thing is your own mindset and how you cope with whatever is handed to you.

Find Linda:

Featured image source: Linda Diak